SCOOP: The missing 8,900 units at Parkmerced and the property's bleak future

Why, after 12 years, hasn't construction started at Parkmerced, one of the largest residential properties in the nation? Plus an update and exclusive on the state of Parkmerced at the end.

Parkmerced, a neighborhood of aging townhouses and high-rises in San Francisco’s southwest corner, is in the midst of a familiar predicament: It’s the site of an ambitious, unresolved housing project with no beginning or end date.

In 2011, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors approved a redevelopment that would overhaul Parkmerced, one of the largest residential properties in the nation. If everything went smoothly, Parkmerced would begin a decades-long process of swapping 3,221 of its decaying units for 8,900 luxurious ones.

But 12 years later, construction hasn’t started. Developers blame a combination of approval and permitting delays that came on the heels of hard economic times. City officials who spoke to me say it’s not that simple and that Parkmerced likely could’ve started building a while ago. In the meantime, San Francisco State University – located near Parkmerced – has built and opened more comparatively affordable student housing, enabling the school to zoom past its main housing competition.

All this leaves Parkmerced – and more importantly, its residents – in an untenable position.

A World War II Era Rush Job

Of all the neighborhoods on the city’s west side, Parkmerced is possibly the most in need of a facelift.

A 1940-1950s rush job originally intended to house servicemen returning from World War II, Parkmerced was always going to age poorly, Parkmerced spokesperson PJ Johnston told me.

A series of neglectful owners haven’t helped matters. By the 2000s, the buildings were in disrepair. In 2000, 53 water pipes burst within 17 months, forcing repair workers to dig unsightly trenches throughout the neighborhood.

Only when Parkmerced Investors Properties LLC, under local developer Rob Rosania, acquired the community in 2005 did neighborhood improvements begin, Johnston said, “from landscape and street improvements to resident amenities, facilities, and events.” (Rosania, it should be noted, has a controversial history of his own – he allegedly acquired properties including Parkmerced only to default on debts and ordered Black Lives Matter symbols removed from a shop he invested in.)

Perhaps the buildings were too old for repairs. Though the buildings are still standing, they’ve been allegedly blighted by moldy, broken water pipes, leaks, and heating issues, among other problems. So at the end of the decade, Parkmerced Investors – which was receiving financial backing from Fortress Investment Group, another investment company – adopted a new strategy: demolish the buildings and start fresh.

Enter Parkmerced Vision, the 2011 redevelopment project.

Attainable or unviable?

A few years after Parkmerced Vision was proposed, Fortress Investment Group sold its stake in Parkmerced to Maximus Real Estate Developers, a Rosania-led owner and developer that’s technically separate from Rosania’s other group, ParkMerced Investors.

If Maximus was good at one thing, it was selling a fantasy. They hired a top architecture firm to design an attractive Parkmerced neighborhood. To sweeten the deal, the developers guaranteed existing tenants in Parkmerced’s 1,538 rent-controlled units replacements at no additional cost, plus a bunch of other perks like an M-line MUNI realignment through the neighborhood, one-third of new units below market rate, an organic farm and a net-zero carbon community.

The developers wanted to make this project as attractive as possible to secure the city’s approval fast. “The worst thing from a developer’s point of view,” Tim Colen, the former executive director of Housing Action Coalition, told me, “is time, which is very expensive.”

Johnston acknowledged the project was “ambitious, but also very powerful and attainable.” For the city’s sake, the project needed to be ambitious. California requires San Francisco to routinely update its housing element, a plan to build housing by a given deadline to alleviate the city’s housing and homelessness crisis. Earlier this year city officials unveiled their latest update; by 2031, San Francisco expects to build 82,000 units, 2,241 of which are supposed to come from Parkmerced.

That Parkmerced still hasn’t started construction more than a decade after developers received approval from the Board of Supervisors speaks to many factors – some in the developers’ control, some not.

For one, Parkmerced couldn’t start construction until developers settled a 3.5-year lawsuit from a local environmentalist group that challenged sustainability goals. A judge dismissed the case in 2014.

After the case was dismissed, the project’s first phase was given a starting year of 2016. Phase one was supposed to add 1,668 more units, 3,500 square feet of retail, street improvements and community gardens, all by 2022. To simplify the six-year phase, the developers partitioned construction into four subphases, which would introduce at least 400 units each.

Then the developers got caught in a lengthy approval and permitting process — not unusual considering the average developer waits nearly two years for permitting from the city. In their last few annual reports, the developers have lamented the city’s inconsistent decisions to demolish or keep a walkway at Parkmerced, a still-unresolved issue.

“The worst thing from a developer’s point of view is time, which is very expensive,” Tim Colen, former executive director of Housing Action Coalition told me.

The developers might need further guidance on a walkway, but they’ve long had the go-ahead to move forward on the project. Maximus just needs the appropriate permitting, which they haven’t asked for since they haven’t been ready to start construction. Further, the project received significant upzoning when it was approved to jumpstart the project, Dan Sider, San Francisco Planning’s Chief of Staff, said. “Ultimately the decision to mobilize rests with the developer,” he told me. The city can only speculate why the developers haven’t started construction; if Sider had to guess, he’d say finances.

Investors gauge the viability of a project by its internal rate of return (IRR), a metric used to estimate an investment’s profitability.

In the years immediately following the Great Recession, investors were looking for low-risk opportunities. So this 2011 project was a tough sell. The IRR was lower than what real estate investors considered attractive, according to a 2011 financial analysis by CB Richard Ellis, a San Francisco consulting firm. When CB Richard Ellis accounted for higher construction costs and an unfavorable market, the IRR appeared grimmer.

If developers did away with some promises, like the 1:1 replacement of rent-controlled units and the MUNI realignment, the IRR would meet or exceed real estate investment standards. According to Johnston, Maximus has nevertheless refused to waver from their commitments. Keeping their promises “may not be easy, or cheap… but it will always be the right thing to do,” Johnston said. There could also be less charitable reasons for sticking to the status quo; namely, to scale the project down, they’d need approval from the Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors, a publicly messy, likely difficult process.

Until quite recently, Parkmerced had a fallback and a trump card for investors: San Francisco State University. The college across the street has nearly 30,000 students it struggles to house annually. With that in mind, CB Richard Ellis’s 2011 analysis suggested rental revenue could serve as a contingency to make the project attractive, despite the low IRR.

Parkmerced vs. San Francisco State University

Whether Parkmerced knew it or not, San Francisco State was also eyeing a housing plan for off-campus students.

While Parkmerced spent the mid- to late-2010s stuck in the mud over approvals, permits and economic woes, San Francisco State announced Future State 2035, a plan to accommodate an anticipated influx of college-aged adults by 2035.

San Francisco State has been preparing for a student housing influx since the early 2000s, purchasing buildings and land directly from Parkmerced, ironically enough. Since the Great Recession, the college has diversified its funding, most notably forming public/private partnerships for student housing.

In 2020, the college constructed Manzanita Square, an eco-friendly apartment-style dormitory. This project also came at the wrong time – right at the beginning of a global pandemic. When learning shifted online, students had no reason to pay for housing on- or off-campus. San Francisco State proceeded with its housing plans anyway.

When students returned to campus in the Fall 2021 semester, newly constructed dorms with an updated gym, courtyard, lounge, and free wifi awaited. If students could score a new one-bedroom apartment at Manzanita Square for $1,944/month, why would they pay $3,300-3,600/month at Parkmerced?

Same old, same old

Parkmerced still hasn’t started construction, particularly because of San Francisco’s poor recovery from the pandemic, “sky-high construction costs, inflation, and supply chain issues,” Rosania wrote to me.

““Ultimately the decision to mobilize rests with the developer,” Dan Sider, San Francisco Planning’s Chief of Staff told me.

None of Rosania’s cited reasons explain why Maximus didn’t start building before the pandemic, when the city had given a general green light for construction. “I suspect [Maximus] can’t admit the project is underwater,” Colen, the former executive director of Housing Action Coalition, said.

It’s unclear whether Parkmerced can take on San Francisco State, its possible partner-turned-competition. Roughly eight months ago, Parkmerced’s vacancy rates reached 30%, Mike Farrah, a legislative aide for District 7 Supervisor Myrna Melgar told me. Johnston contests this number, though he didn’t provide a figure of his own.

For what it’s worth, Judson True, the Mayor’s Director of Housing Delivery, is optimistic about the Parkmerced project. “I see momentum in the project's ongoing efforts to secure various permits and approvals [for later subphases] from City departments,” True wrote to me. True works on all large-scale development agreements, including Parkmerced.

And, as Farrah was quick to remind, “[The real estate market] always comes back. “Real estate is always a good investment in San Francisco.”

Perhaps – but when is the rebound coming? San Francisco is desperate for more housing, and the current market isn’t cooperating. Veritas, the city’s largest landlord, recently defaulted on a $448 million loan. The city is reportedly working with Maximus to find more “tools” to revive the project – including novel funding options – but the clock is still ticking, and current residents are still living in aging buildings.

A full 12 years after securing approval from the Board of Supervisors, the blame game at Parkmerced remains, and its developers face the same fundamental problems. Chief among them, and all that matters anymore, is this: When, if ever, will Phase One of construction commence?

UPDATE: Days after my report on the state of San Francisco’s Parkmerced — originally published on SFGate (02/27/23) — Aimco announced it will sell its $275 million mezzanine loan for $168 million — a 25% loss.

Aimco is a publicly-traded real estate investment trust based in Colorado. They were not planning any dispositions in 2023, according to a letter to current and prospective stockholders from last week.

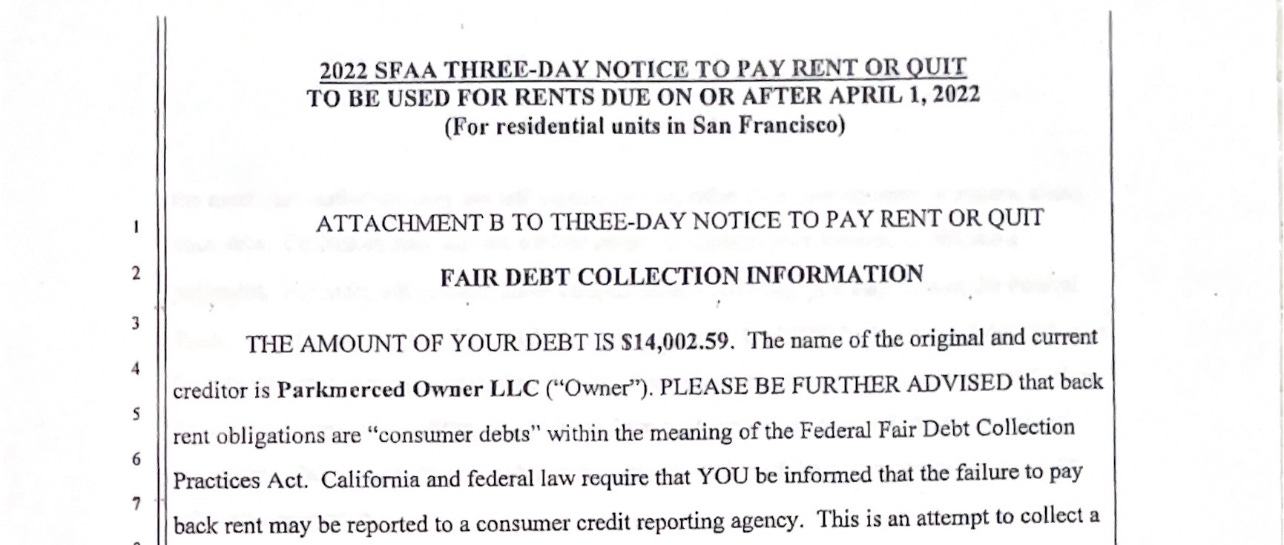

SCOOP: Proposition M, a vacancy tax, will take effect in 2024. Amidst this and an ongoing eviction moratorium, Parkmerced Owners LLC filed eleven unlawful detainers — a secondary step in the eviction process — earlier this month. Public records I obtained show that these unlawful detainers were filed for over $11,000 of unpaid rent from April to August 2022. Some delinquent tenants have lived at Parkmerced for over a decade. It appears Parkmerced is merely initiating the eviction process, though three-day notices to pay rent or quit were already issued.

If Parkmerced doesn’t fill these vacant units fast, the vacancy tax may force the property into a catch-22. If they successfully evict these delinquent tenants, they may still lose just as much money maintaining a vacant unit. And with higher-quality competition, it’s unclear if Parkmerced can replace these delinquent tenants anytime soon.

I live in Park Merced. I was told a few months ago by Kris the GM that there were over 900 empty units and so many squatter break-ins they couldn't keep up.

Also, per ny former neighbor (a PM employee who quit in disgust) that they've spent the last several years heavily writing Section 8 leases, which probably explains the massive crime spike.

Additionally, Parkmerced isn't just evicting for April-August 2022.. they're also evicting for debt covered under the Ordinance 34-22 moratorium. PM's been on a vicious harassment campaign since the pandemic started, despite gleefully accepting state and local assistance.